Princeton’s privilege: rethinking public school funding

October, 2021

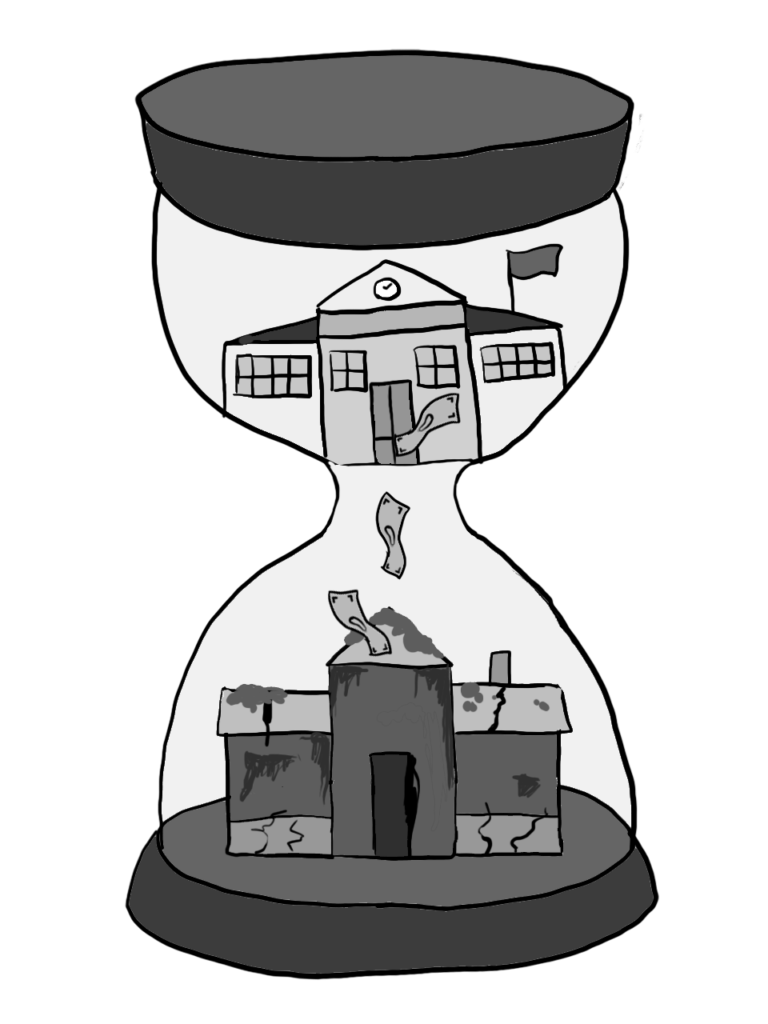

Pulling up to school in luxury vehicles with five-dollar coffees in hand, many PHS students are a far cry from normal. The opportunity to go to farmers’ markets in our senior parking lot on Thursdays and take courses at Princeton University are symbols of comfort and wealth. Especially compared to the school districts around us, PHS is a pillar of privilege. And while much of this privilege is used for good, it’s still strange in comparison to the districts around us. While we got MacBooks, West Windsor-Plainsboro North got Chromebooks, Monroe got iPads, and some schools got nothing. On top of that, some schools have crumbling infrastructure, an issue that they can’t even afford to solve. Meanwhile, Princeton Public Schools has begun construction on a multipurpose studio for yoga and dance.

Solving this pressing issue of inequity doesn’t completely fall on PPS, though spending millions on construction alone is still quite a contentious choice. Rather, American public school funding is what needs to be scrutinized. Education is supposedly a human right, but the government rarely supports this, chronically neglecting struggling public schools. And, like always, it comes down to the policy. The funding of American education is anything but equitable. A large part of public school funding comes from property taxes, a source of money that varies by location. Low-income areas with low property taxes will have little financial support for their schools. Therefore, quality of education is determined by geographic distribution of wealth. Education is also the foundation of success, yet we withhold quality education from people who need it the most. It’s impossible for low-income Americans to lift themselves up out of poverty without quality education, but our current system almost ensures social stagnation. Unless property taxes in poor neighborhoods radically increase (which they won’t, because living in poor neighborhoods isn’t exactly desirable), these schools will simply never get funding.

graphic by [credit name = "Emily Qian"]

But the United States is one of the only developed nations that relies on property taxes as heavily as it does for public education. Many other countries have similar but more effective mediums of securing money for public schools. For instance, some compensate with national or federal aid; their public school financial support comes from supported legislative acts and federal-level taxation, not just from local sources. In the United States, though, much is left up to individual states. Just by looking around us, we can see the necessity for a policy shift. The property value in Princeton is significantly higher than the surrounding towns (just check Zillow), and as a result, our education is significantly better. Students in under-funded schools often feel that their teachers don’t care; at PHS, however, teachers’ passion for learning is evident. Even the resources we get compared to the surrounding schools is baffling. With some exceptions, PHS activities remain well-supported across the board. From clubs to athletics to the arts, student life is highly funded and prioritized by the school. Being able to open your Instagram and see our orchestra in Italy is typical of Princeton High School; bands in most public schools outside of our district couldn’t feel the same. Access to quality education is directly associated with socioeconomic status, and classism in America underscores nearly every issue discussed in Congress. Representatives tend to focus on the hot-button issues while neglecting substantial reform. It is our responsibility to vote in legislators who genuinely care about righting the wrongs in the education system. If we value our education and the privilege it affords us, we should aim to ensure that everyone has access to an equal and quality experience. Education and democracy go hand in hand because both are emblematic of the human capacity to achieve more. So if we truly value our trips to Italy and our sports resources, we need to vote with education in mind.