Lunch is for eating, not cooking

April, 2025The lunch bell rings at 11:33, and fourth period ends as hundreds of students pour out of classrooms and into the halls of Princeton High School. Some students head to the library, while others head to the guidance office. Some just walk laps — earbuds in, heads down, skipping lunch for the third, maybe fourth day in a row. It is not a diet. It is not a protest. It is not always a choice.

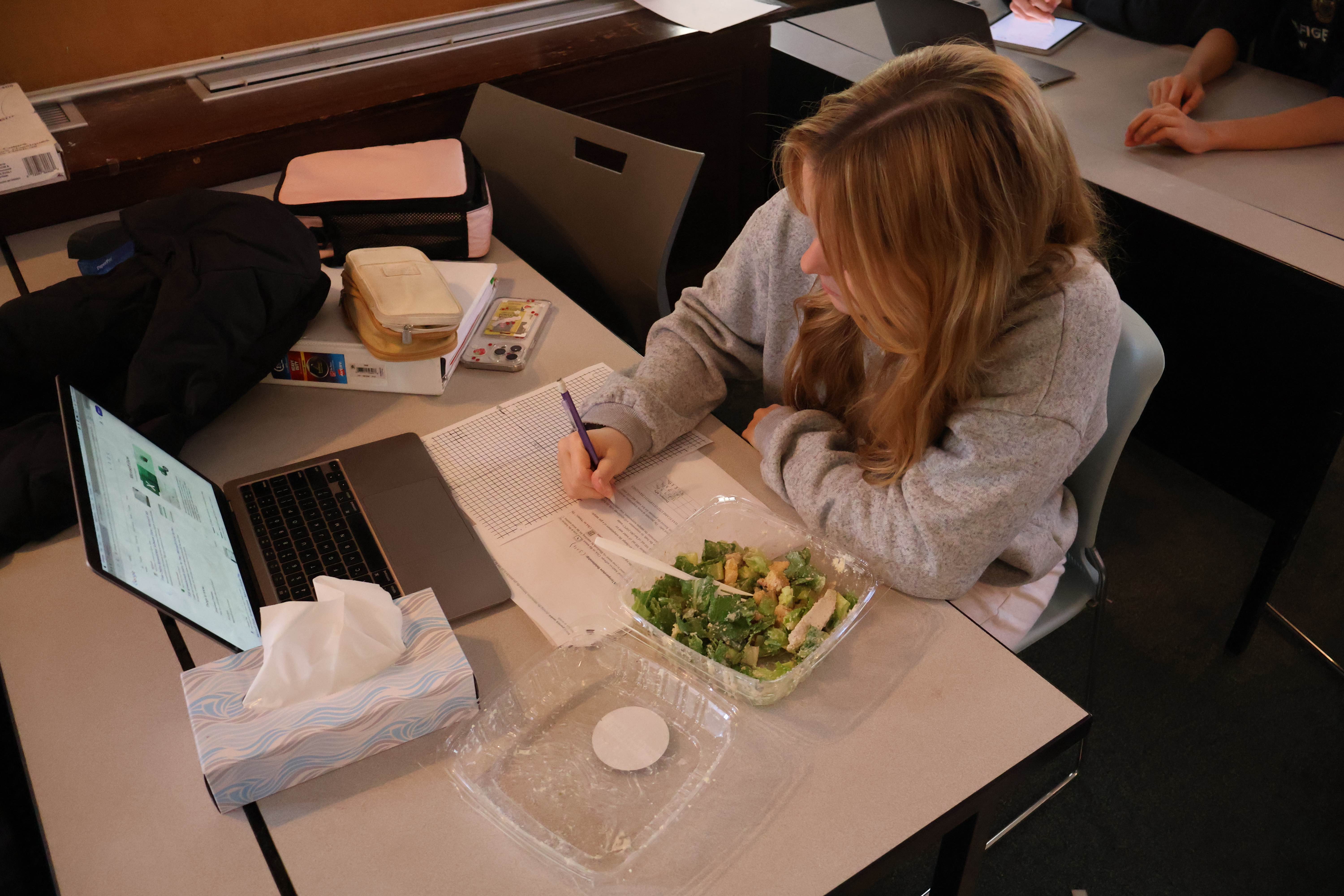

For too many students, lunch has become optional. Not because they are not hungry — they are — but because 35 minutes is not enough time to eat, finish an essay, ask a teacher a question, and review for the quiz they have next period. In the past few years, there has been an unhealthy exaggeration of high school performance and how it affects the futures of these students. Because of this, when given the choice between nourishing the body and “getting ahead” in their studies, the choice seems trivial.

This is not just a PHS problem. According to a 2020 national survey by Yale University, 75 percent of high school students report having negative feelings toward school. The general sentiment seems to be that these students feel negatively towards school because of apathy or laziness. The truth, though, is that these students are under copious amounts of stress, driving them to have these negative feelings.

A New York Times article written by Tim Donahue stated that “we [as a society] have pushed high school students into maximizing every part of their days and nights.” Students feel like they need to do more and more in order to stay afloat. Self-care takes a backseat because students feel like they need to do so much in order to distinguish themselves. They need to get perfect grades, take the hardest classes, be a part of every extracurricular under the sun. Of course, under all of this pressure, physical needs become an afterthought.

The way students cope with this stress is not always visible — but it is often unhealthy. Skipping meals, sleeping in fragments, and studying at midnight. It becomes a game of sacrifice: what can be dropped to make room for everything else? For too many, the answer is lunch. A study from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that students given less than 20 minutes to eat consumed significantly less food and nutrients. When the body is not given the nutrients it needs to function properly, productivity drops. This, in turn, harms students’ academic performance. When students are skipping meals just to keep up — when they feel they have to choose between eating and succeeding — something is wrong with the system, not the student.

We need to stop pretending that this is normal.

Lunch should not be a luxury. It should not be treated as expendable. It is time — real, uninterrupted time — to eat, decompress, exist as something other than a GPA.

So the questions posed are, how do we take back our lunch periods? How do we take our lives back from the grind that academia has instilled in us? There is no single fix, but there are places to start — both as individuals and as a school.

At a school-wide level, the goal should not just be more time. It should be better use of the time we already have. Lunch needs to be protected. No required meetings, no mandatory makeups, unless a student chooses them. The school can also help by making lunch more accessible — a pre-order system or even a simple form could cut down the lines that push students away. And if we are serious about student wellness, the message needs to be loud and clear: eating and resting are not optional, they are essential. Teachers and administrators should say that out loud. Not just in emails during Mental Health Week, but every day, in how they schedule, how they speak, and what they prioritize.

But change cannot just come from the top. It starts with what we do, too. That might mean bringing food from home instead of skipping lunch. Taking ten minutes to sit down and actually eat. Using free periods to slow down instead of squeezing in more. Outside of school, it means setting boundaries — around sleep, around work, around the pressure to always do more. And maybe most of all, it means shifting how we think. Getting the perfect grades and getting into a top college are not the most important things in your life. More than that, needing rest does not mean you are failing. Taking care of yourself is not weakness — it is proof that you are still trying to live, even in a system that tells you to do the opposite.

So when the lunch bell rings at 11:33, you do not need to run. You can stop. You can eat. You can let that be enough.