Why inclusive initiatives are failing in the academic space

April, 2025

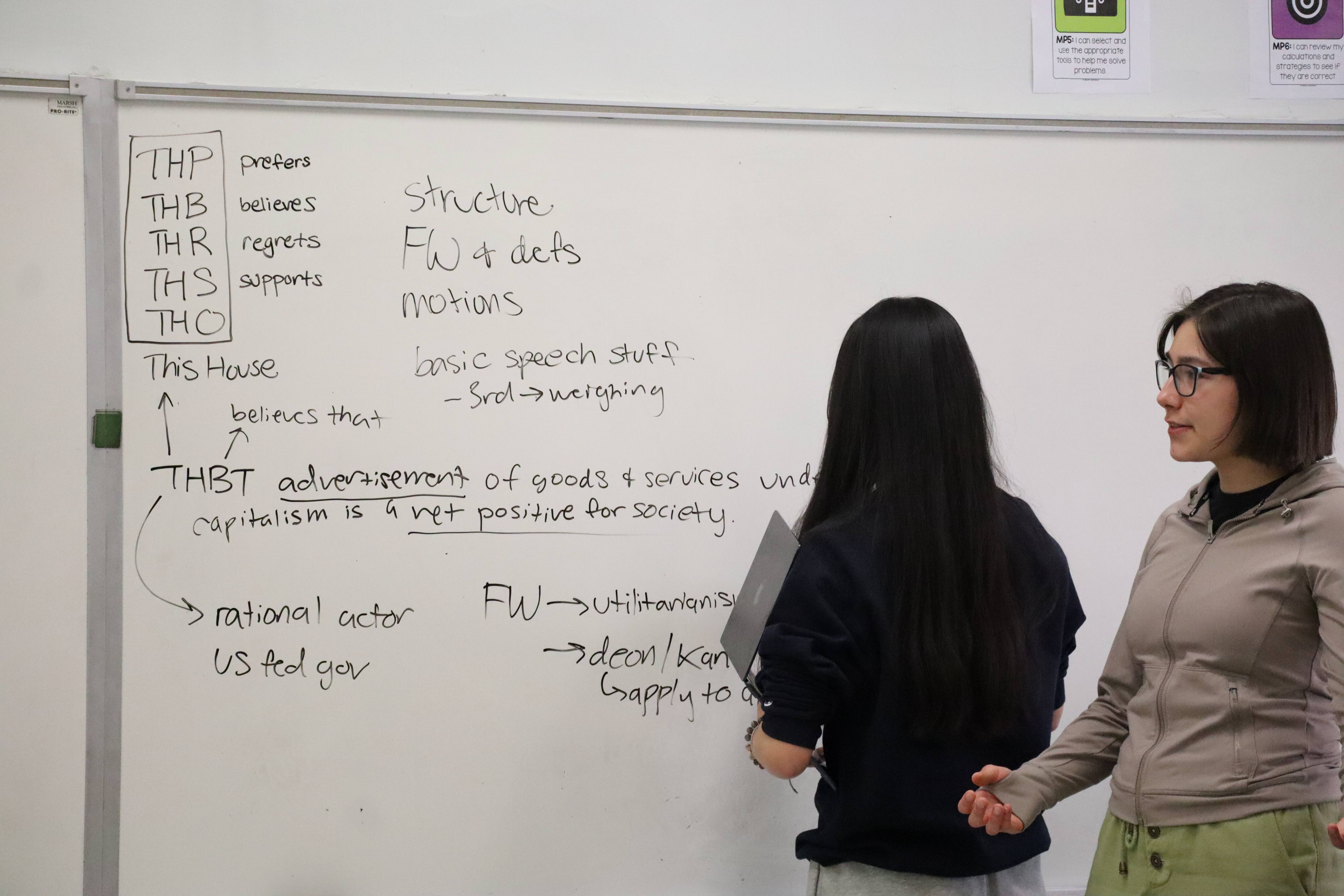

Photo: Katherine Chen

“Stop GENDER DISCRIMINATION in debate,” reads the cover slide of the hit 2024 Instagram post by the Debate Hotline. This particular post collected (at the time of writing this article) a whopping 2,164 likes and 247 shares, making it probably one of the most notable moments of feminist activism in the high school debate space in recent years.

Any debater with an Instagram account would likely recall the viral impact of this post. Across my feed, debaters of all genders shared the post, creating a powerful moment of solidarity. This moment mirrored activism in other competitive academic spaces — from the #WomenInSTEM movement addressing gender gaps in mathematics competitions to the Women’s Chess Initiative highlighting similar disparities in chess. Nonprofit organizations have proliferated across these disciplines, each focused on promoting gender equality in their respective activities. In debate specifically, feminism has become perhaps an integral movement. Yet despite this widespread activism, gender disparities persist across all these academic spaces. In mathematics, women still represent less than twenty-five percent of International Mathematical Olympiad participants. In chess, women account for just eleven percent of rated players worldwide. In debate, the disparity remains since the viral post. This raises a critical question that transcends any single discipline: Is our current approach to addressing gender discrimination in academic competitions actually effective?

To approach an answer, we can examine the Debate Hotline post and how the debate space handles inclusive activism. The post features quoted testimonies from female debaters describing misogynistic social encounters they have experienced: “At the Harvard tournament, I advanced in out-rounds. When a male friend of mine found out, he congratulated me by saying ‘have my babies,’” recounted one anonymous submission. Beyond these accounts, the post presents three key statistics: women are 18.8 percent less likely to win Varsity elimination rounds, 30 percent more likely to quit debate altogether, and notably absent from half of all national circuit finals. They end with a call-to-action urging debaters to sign a petition that demands the NSDA to implement mandatory judge bias training.

The message of the post reflects the message of the overall feminist movement in debate: biased judging leads to female debaters losing rounds, which drives them out of the activity, ultimately hurting their academic and life opportunities. This rhetoric also follows through in Fem-Kritiks, a popular argument (usually made by female debaters) that urges the judge to drop the opposing team (usually male), and for the opposing team to forfeit the round. This is done in order to even out the win-loss disparity by addressing judge bias.

The problem with this widespread rhetoric is that it is only partially true; a closer look at Yi and Nie’s 2020 study “An Empirical Study of Gender Differences in Competitive High School Debate” reveals something crucial. In Varsity rounds, the study found “a large difference in win rates between teams of different gender compositions, with female-female teams 17.1 percent less likely and male-female teams 10.0 percent less likely to win a debate round against male-male teams.” However, they also found “no gender gap in win rates for novice debaters.”

If the thesis of female push-out being due to judge bias is to be believed, why is there no sex disparity in novice round results? The study follows this discovery by suggesting that “the disparity does not occur from innate entry ability differences, but rather appears alongside experience in debate.” In the results section, Yi and Nie continues that “some possible causes of this gap result from a female debater’s environment: potential bias in the amount of resources allocated to competitors by coaches, the gender-hostile environment of a team, or the effect of the perceived stereotype of the activity, to name a few examples.”

This pattern extends beyond debate and into other competitive academic spaces. Chess, for instance, has implemented structural solutions by creating women-only sections and tournaments since 1927. Yet despite these institutional changes, the gender disparity in chess still exists today. The underlying cause mirrors what we see in debate, which is a hostile social climate. Female chess players consistently report implicit exclusion from the broader chess community, which pushes them out from participating. In many academic environments, female participants describe being excluded from study groups, having their contributions minimized, and facing heightened scrutiny of their abilities. These experiences, not competition results alone, ultimately drive many talented women away despite their proven capabilities.

Although misogyny and other forms of inequity is a systemic problem in academic spaces, we need to stop focusing on that — however counterintuitive it sounds. Exclusively deeming the issue to be systemic is how we arrived at our current position. It removes responsibility from the individual. If you are someone who cares about and wishes to solve inequality in the academic space, it is time to address the issue on a personal level: how you deal with and react to hostile situations. Have you stood up for others? Have you excluded team members from resources? Have you actively denounced crude, inappropriate behavior? Have you stopped perpetrators from participating in leadership?

I’m not demeaning current feminist initiatives. Their focus on institutional change remains important. But perhaps we need to focus elsewhere; perhaps our activism has become too copy-paste, too shallow, too performative; perhaps we need to look elsewhere, deeper, within ourselves. Our efforts must address the social climate that shapes our activity from within, not just the institutional structures above. While continuing to advocate for structural change, let’s recognize that creating truly inclusive spaces begins with us.